Referring to a multitude of historical archives, an engaging new exhibit creates a stage for the untold stories of European history

By: Teresa Valenton

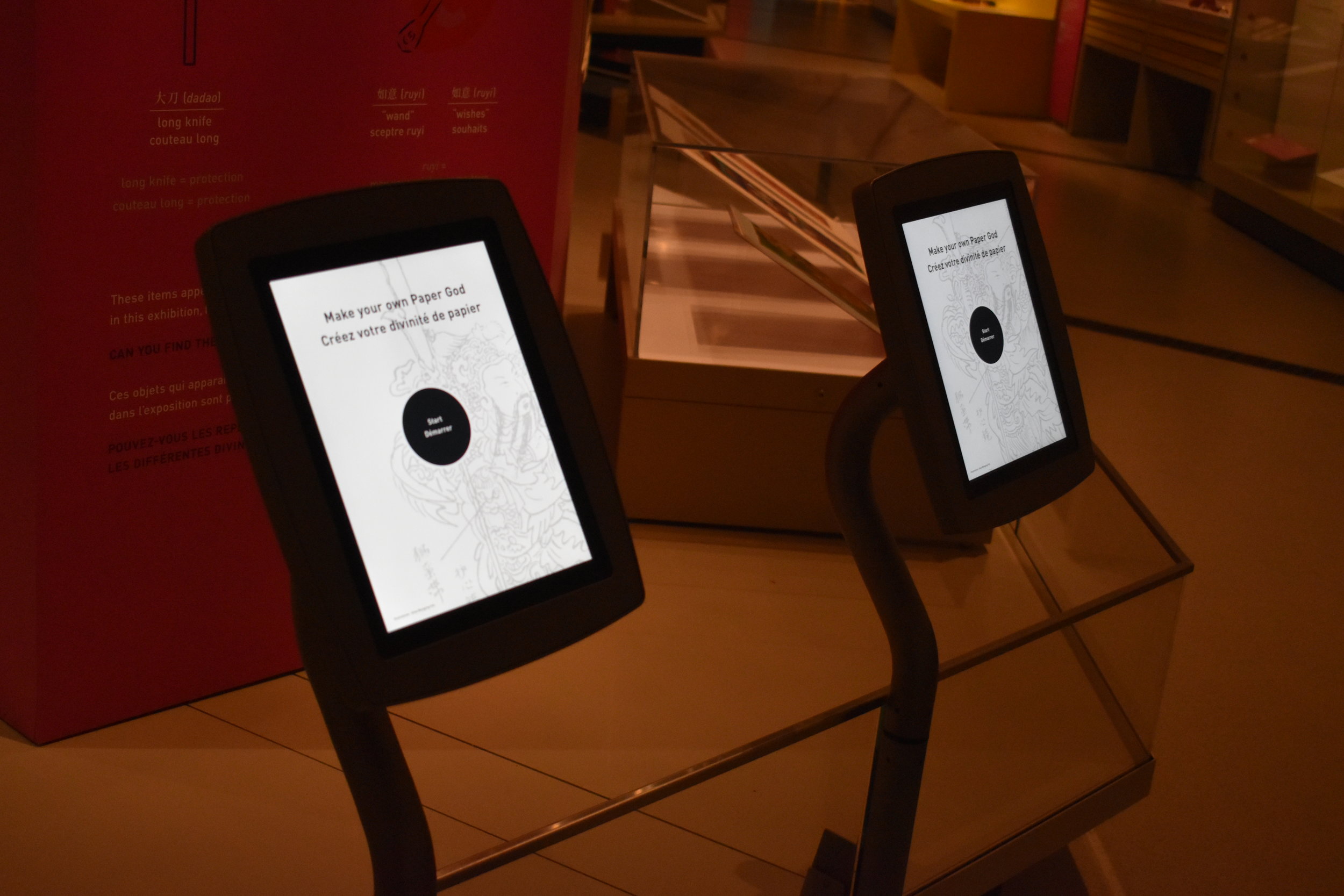

Gibson invites audiences to immerse themselves in his exhibition through the use of familiar mediums such as stickers, posters and furniture. (Teresa Valenton/CanCulture)

By creating interactive spaces for the general public to immerse themselves in, a New York-based artist facilitated an accessible space for marginalized communities at Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

On March 10, MOCA launched their spring exhibitions featuring headlining artists such as Shirin Neshat with Land of Dreams, Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Summer and Jeffrey Gibson’s I AM YOUR RELATIVE. Throughout each floor, the artists present their ideas through unique mediums, while a recurring theme of connection weaves itself through them all seamlessly.

As each artist shares “emotional portraits” by immersing viewers into the art, MOCA has become a space for self-exploration and enlightenment.

At the unveiling of his first exhibition at MOCA, Jeffrey Gibson, an interdisciplinary artist based in Hudson, New York and member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and Half Cherokee, transforms the first floor of the gallery into a visual archive to uplift Indigenous, Black, Brown and queer voices.

Situated on the gallery’s free admission first floor, Gibson utilizes historical archives and bright stages to recall the ways in which history has been told.

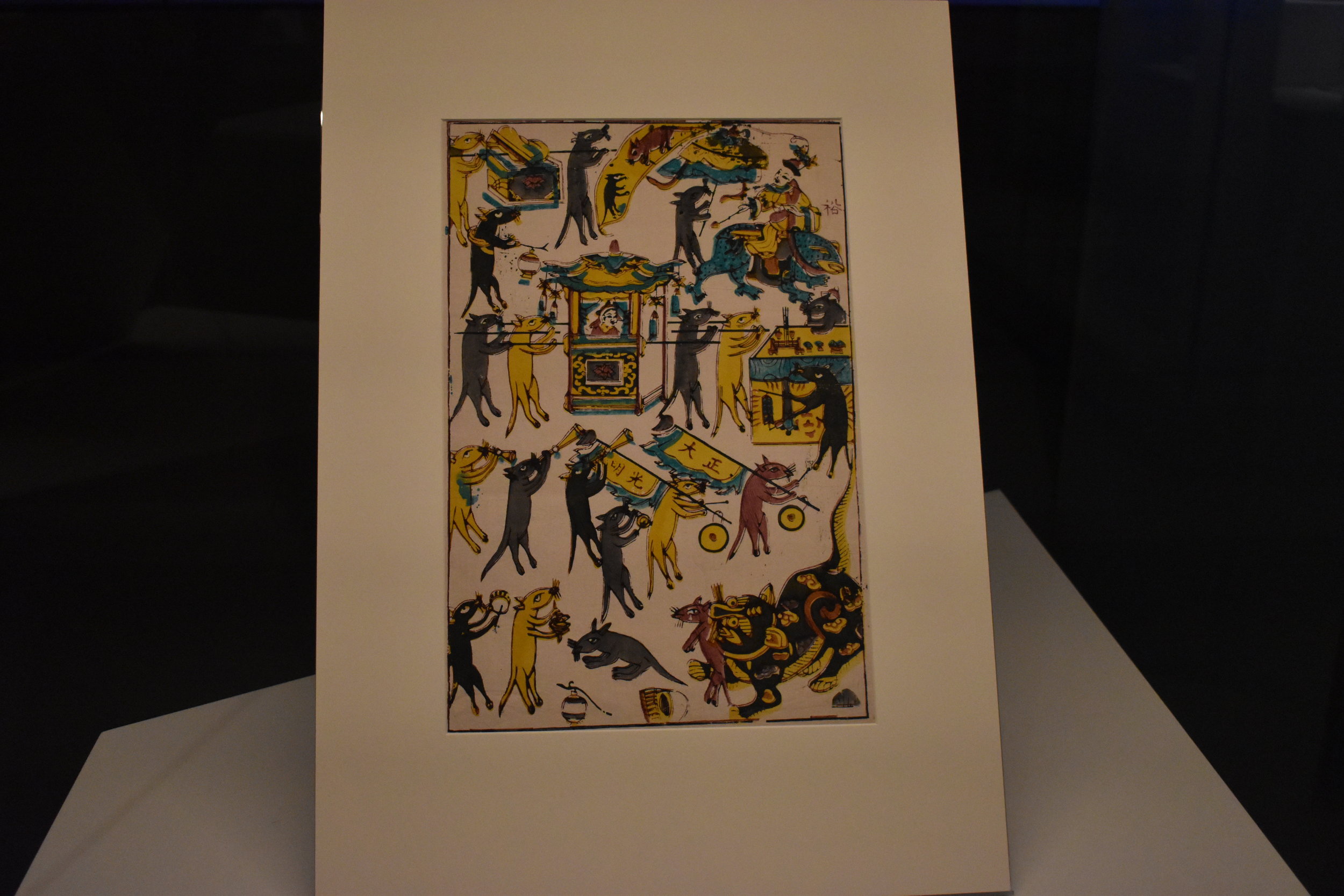

Rendering photographs of Indigenous, Black, Brown and queer people, Gibson faciliates a space to provide comfort to those who have felt silenced. (Teresa Valenton/CanCulture)

“Knowing that this space is open and available and free to the public was something we wanted to make available for multiple ages. I guess this was an accessible way for people not to feel intimidated by an art space to make them feel comfortable,” said Gibson.

As the exhibition unfolds over the upcoming months, performers such as Amplified Opera, a Toronto-based opera company, and Emily Johnson, an American dancer of Yup’ik descent, will bring in other narratives of history through unique performances.

Inspired by his own artistic practices over the last 15 years, Gibson incorporated furniture that viewers could curate experiences out of. Incorporating pillows into each “stage,” he encourages viewers to become comfortable within his work.

Referencing his previous work To Name An Other: Call for Performers by the National Portrait Gallery in 2019, Gibson presents a crossover between art and audience involvement. The craft comes from allowing individuals to be observed through their actions, Gibson said.

Gibson invites his audience to partake in his exhibit by using comfy, colourful pillows. (Teresa Valenton/CanCulture)

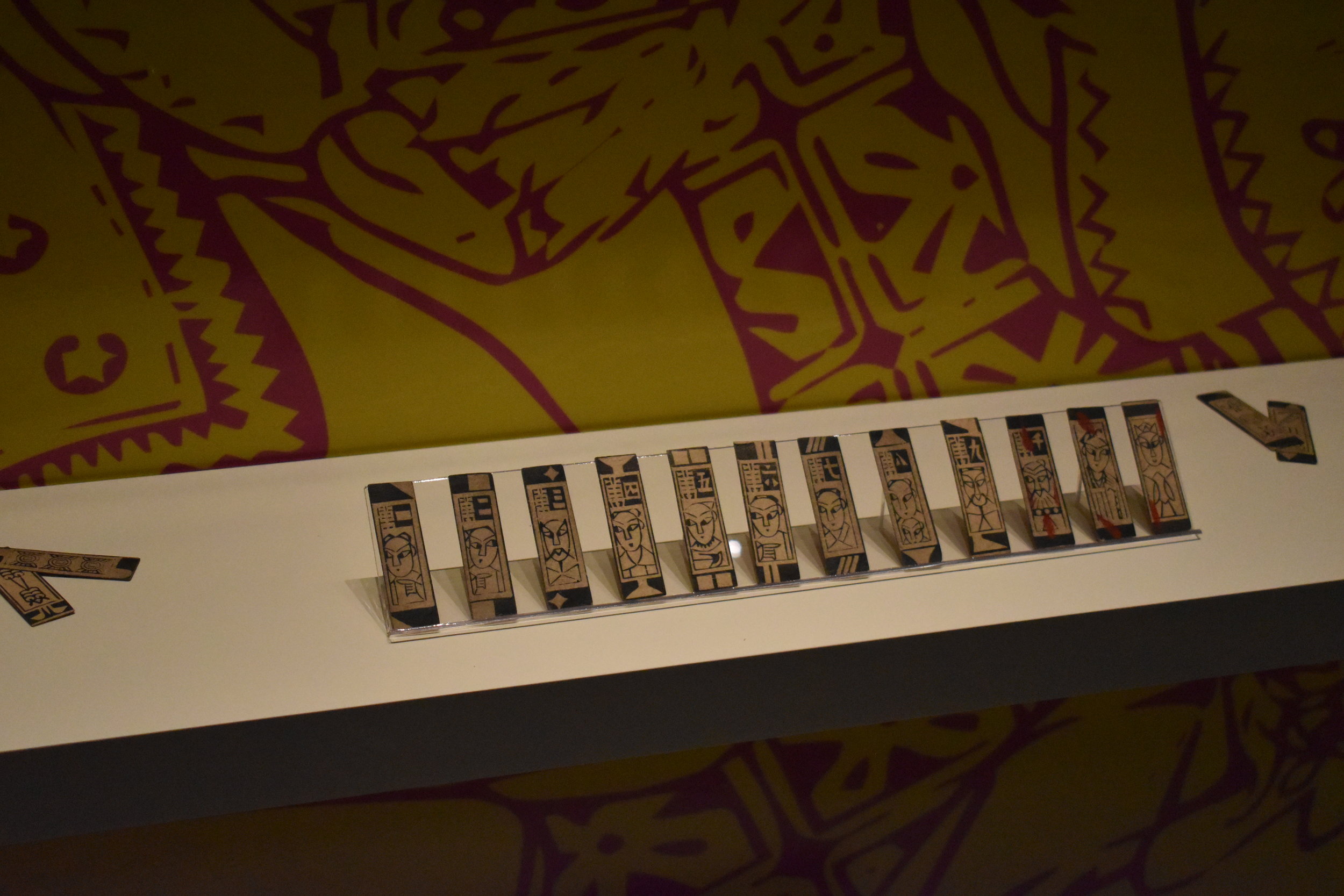

In utilizing public spaces, Gibson presents history through the use of public archives. While referencing stories rooted in Indigenous cultures of the Americas, he gravitates towards certain materials such as stickers and rendered photographs. When reminiscing about the poster walls of his teenage bedroom, Gibson relates it back to the found materials for I AM YOUR RELATIVE.

“I like the negative spaces as other information peeks through, and then the local contributions that we receive will enter into programming to see what they have contributed,” Gibson said.

Though the pandemic took an effect on the production of this series, reconfiguring ideas and communicating with performers took roughly 18 months, Gibson said. All images that were used had to be formatted along with the stage designs in accordance with his creative vision.

Travel restrictions slowed down the momentum but his team was eager to pick up the project. All members took precautions and relied on transparency throughout the project, forming a community in the process, Gibson said.

When considering perspective, Gibson encourages viewers to take enjoyment in his work, “I think it’s a place for people who have differences who believe that these differences are tremendously rich and add to our culture.”

Continuously shocked at the prejudices that remain intact, Gibson feels as if the treatment of Black, Brown, Indigenous and queer folks should have culturally progressed. However, with the relationship between research and art, Gibson is reminded that images can appear both abrasive and empowering to different audiences.

Presenting the relevance of this piece, Gibson marks history through a multifaceted expression of today.

“There are emotions; there are facts; there are lies. So I see it as generating media to help describe the moment as if someone was looking back at it.”