This new cookbook goes beyond mouthwatering food recipes by diving into culture, history and agriculture

By: Anna Maria Moubayed

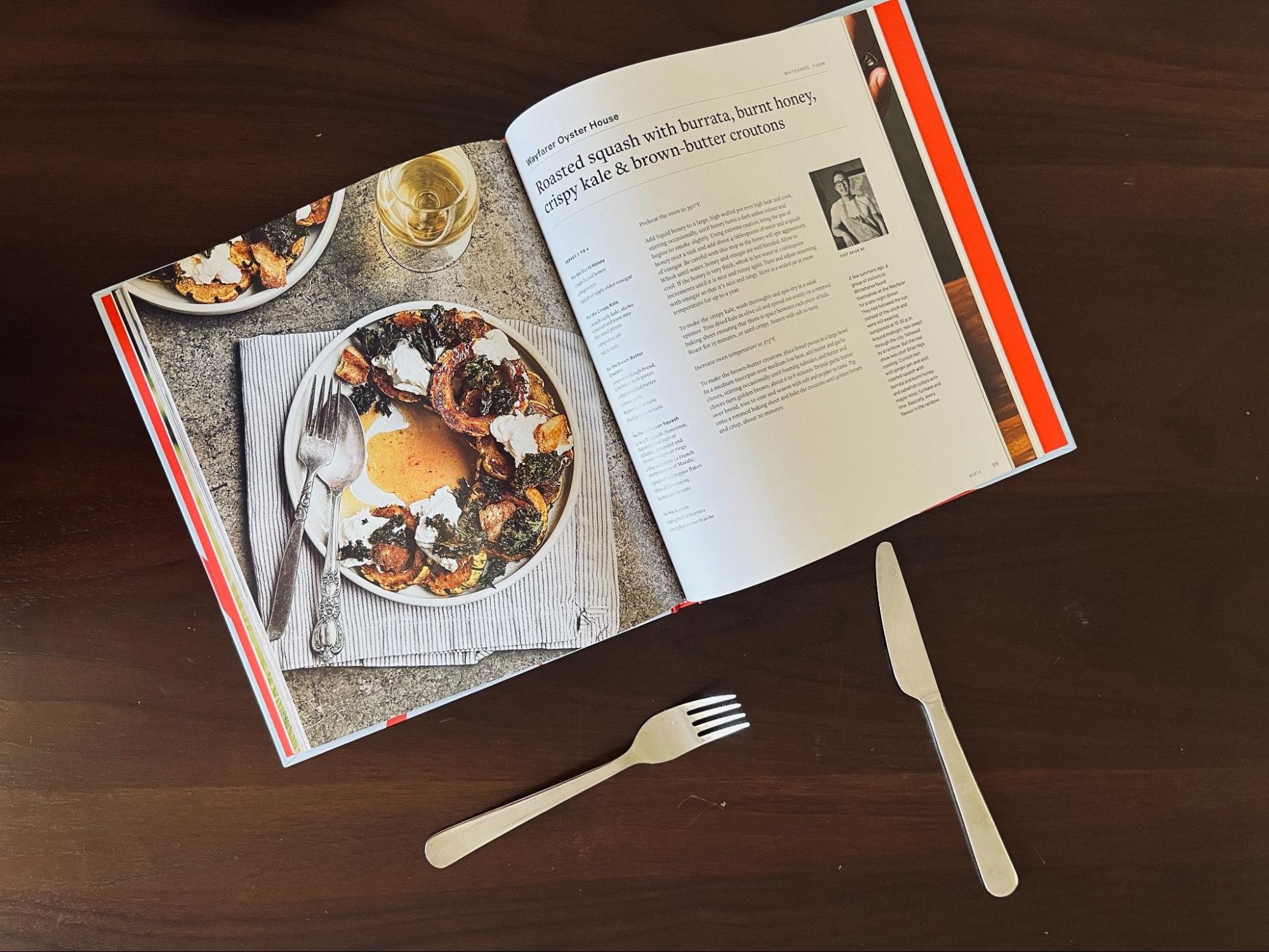

A featured recipe in Canada’s Best New Cookbook by Wayfarer Oyster House, a restaurant in Whitehorse, Yukon. (Anna Maria Moubayed/CanCulture)

I went to Indigo to get Canada's Best New Cookbook in the flesh, and I, along with a lovely worker, had trouble finding the book. Turns out Canadians are already enjoying this “new” and “best” cookbook, and it is selling fast.

The book itself is a partnership between Air Canada’s enRoute, a site that helps travellers navigate hotels and restaurants in different cities– and, well, makes you wish you weren’t sitting here reading this article right now– and Destination Canada, a corporation that helps develop tourism in Canada.

The cookbook is written by James Beard Award-nominated writer Amy Rosen, but also features contributions from other Canadian writers like Alexandra Gill, Julie Van Rosendaal and Heather Greenwood Davis.

It contains recipes from more than 30 restaurants, including the top 10 winners of Air Canada enRoute's Canada's Best New Restaurants program from the past 20 years.

Within the first few pages, a “glossary” of ingredients appears, which help define each Canadian province by positioning them within fascinating food contexts. For example, did you know that quality wheat from Manitoba is exported to over 70 countries, from Iran to Japan? Or that Saskatchewan is the world’s top exporter of lentils and produces 95 per cent of Canada’s supply? Or that fresh lobster is available in Nova Scotia 365 days a year?

The book is sectioned by different parts of Canada: Atlantic, Central, Prairies, North and West. Each section has its own specific recipes and stories.

The recipes come from different chefs from different cities. They have an ingredient list and detailed instructions on how to prepare the dish. Each recipe has a perfect-looking picture of the dish that shows the end result. The mouth-watering pictures are sure to inspire anyone to jump into the kitchen and start cooking, or check their bank account to possibly book a trip to the chef’s restaurant.

The recipes are a mix of sweet and savoury and could amount to a full-course meal, starting with some appetizers, amuse-bouche or soup, followed by the main course and finished off with sweets and drinks.

Making food, whether professionally or simply to cook for your family, often creates stories, memories or even history that passes down from one generation to the other along with the recipe itself.

In this modern take on a cookbook, there are interesting and heartfelt stories about the preservation of different cultures and cuisines, how different cuisines have grown in Canada, the business struggles in the food industry, and Indigenous history scattered amongst the recipes. This provides an unexpectedly refreshing mix of content that connects the reader’s emotions to the food.

The first of the stories, titled “A healing food journey, beginning with bannock cooked in the sand” by ILona Daniel talks about the traditional Mi’kmaq territory on the north shore of Prince Edward Island. Even though the Lennox Island First Nation situated there was the first reserve in Canada to be owned by its own community, the Mi’kmaq of Lennox were forbidden to perform any traditional practices by the local church for a long time. In an effort to keep these traditions alive, practices had to be conducted secretly, yet in plain sight, thus giving rise to the bannock cooked in the sand.

Bannock was not always prepared in the sand. This new tradition comes from times when preparing bannock was seen as a practice of culture. To keep the bannock a secret, the Elders of the community would make the dough and keep it in a hole under firewood. Then, they would cover it with sand and put the firewood back over the bannock until it was cooked.

Another one of the stories titled “An epic taste adventure on Surrey’s spice trail” focuses on Surrey, home to the second largest South Asian community in Canada (next to Brampton, Ontario). The author, Bianca Bujan, is on a hunt for the best South Asian food the city has to offer.

Bujan visits Chaska, where the small, unassuming space is contrasted with a big and bold menu, with in-house made spices and marinades. She also visits Kerala Kitchen, where Sujith Rj, a former Fairmont Hotels chef, now lives his dream of running a restaurant that features his childhood foods. Here, dosas dominate the menu. She describes the crepes as “airy” and “crispy.” Bujan goes to My Shanti, where the chef and restaurant owner Vikram Vij guides her through the two-pronged eating process of gol gappas. When she arrives at the restaurant, she is greeted by Vij with a warm smile and his hands in a prayer position. “My Shanti means my peace, … and my home is where I find peace.’' In his home away from home, the restaurant’s menu pays homage to the diversity, regionality and richness of South Asian cuisine.

There’s also “Nunavut’s craft beers and landscapes quench thirsts and soothe souls” by Susan Nerberg. It talks about how the floe edge, or sinaaq in Inuktitut, is where open water meets the ice still attached to the shoreline. For a few weeks each year, Nerberg writes, the floe edge becomes an assortment of delight, with an “eruption of life” on its shores. Perhaps this is why the Nunavut Brewing Company chose to launch in Iqaluit, with a beer named Flow Edge, writes Nerberg.

The government-run wine and beer stores are limited since supply is based on container ships arriving with cargo during ice-free summers. “Our goal is to make a local product that supports the local community,” says Jason Oldham, NuBrew’s general manager.

At the taproom, a customer’s senses are already at work. From the bar stool, the iceberg-white brew hall is visible, with the aromas of hops, yeast, malt, and barely reaching the tip of the nose, writes Nerberg. The red ale is called Aupaqtuq, Inuktitut for “red.” Frob Gold, the strong ale, comes from Martin Frobisher. Nilak, one of the regular beers on tap, comes from the Inuktitut word for “freshwater ice.”

“There are northern lights and a midnight sun pouring glitter on the bay and tossing sparkles on the hills. There’s the land to feed the senses,” she writes.

This book does a good job of bringing the art of modern-day cooking in a multicultural society to the reader's kitchen. It truly takes the reader around Canada and provides stories behind certain food scenes while introducing them to new restaurants, skillful chefs and their delicious recipes.