Toronto Metropolitan University students take advantage of the city’s vast multicultural food community to battle homesickness

By Kyana Alvarez (with contributions from Hssena Arjmand, Olga Bergmans, Sierra Edwards, Abbie North and Vanessa Tiberio)

It is a brisk and gloomy November day, but a warm Brazilian carrot cake (from an even warmer Brazilian food vendor) melts away the cold. Despite being in the middle of downtown Toronto, the sweet treat never fails to teleport Roger Castelo back home to Brazil.

As international university students move away from their countries to pursue education, many must give up what they know as home. For some international students at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU), food has become a crucial outlet for battling homesickness and exploring their culture away from home.

Castelo moved to Toronto in 2021 to study professional communications at TMU. He was drawn to Toronto’s diversity and welcoming atmosphere.

“Toronto was the perfect place because it has a lot of different cultures coming together and I'm[is] very passionate about language… Being here and learning English and French is also a great asset for me,” says Castelo.

Roger Castelo moved from Brazil to Toronto, Canada in 2021, to study at Toronto Metropolitan University (Kyana Alvarez/CanCulture)

Despite living “a dream come true” by studying in Toronto, Castelo says he misses his home, his friends, his family and his culture deeply.

Homesickness is a common and powerful emotion among international students. According to a study from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information, about 94 per cent of students experience homesickness during their undergraduate degree.

“I have a difficult time as an international student. I don't feel like that's recognized enough, having that identity crisis,” says Sofia Villar Saucedo, a third-year RTA School of Media student.

Villar Saucedo identifies herself as a “third-culture kid” because she grew up in Mexico, moved to the U.S. for two years, and then spent a decade in China before coming to Canada to attend TMU.

However, both Castelo and Villa Saucedo have an almost fool-proof method for comforting their homesickness — eating foods from their home countries.

““Food is almost like another language. There is so much power in the dish you eat, and there’s always a story behind it. There’s a heritage, culture and history carried in the dish.””

Because of Toronto’s extensive diversity, international students like Castelo and Villa Saucedo don’t struggle with finding authentic foods from their home countries.

However, not all international students have the means to find comfort in food. There is a growing number of students experiencing food insecurity, and international students are often overlooked, says Fleur Esteron, a TMU sociology professor.

“Food security also includes the cultural side of food and the social aspects of food [along with the financial aspects]…” she says. “International students’ prevalence of food insecurity might be higher [because of the costs of moving here], and because they’re missing that cultural and social side [of food].”

She says It is necessary to increase financial assets for international students to combat food insecurity - including cultural and social aspects.

More than 190,000 people immigrated to Toronto from 2016 to 2021, according to Statistics Canada. Like the countless other immigrants in Toronto, Castelo and Villa Saucedo enjoy finding different foods from their home in the city.

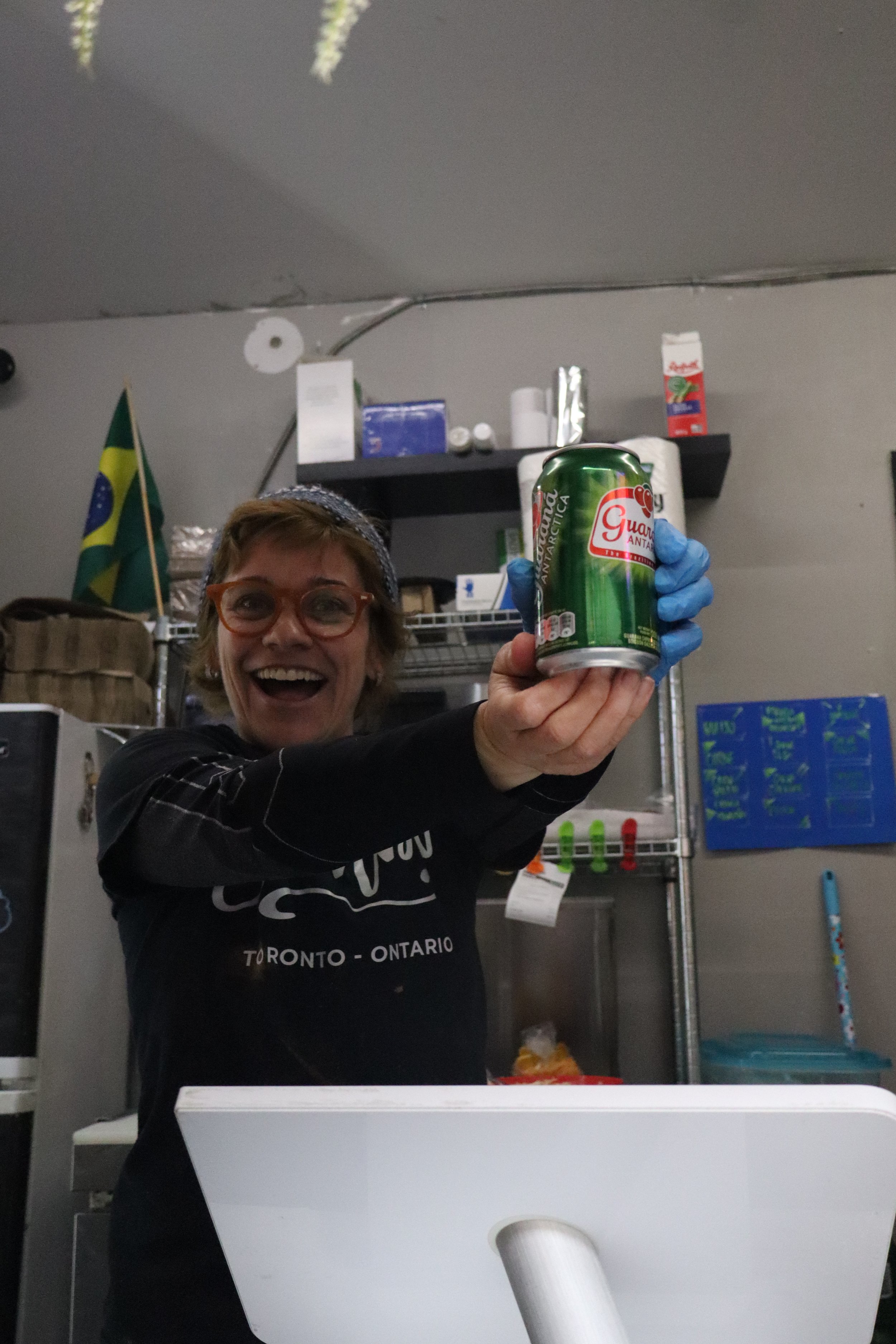

“There's a place close to campus… It’s called Samba, and they sell a lot of Brazilian street foods. So, whenever I’m feeling very homesick or want something that brings me back home, I always go there to try their food,” said Castelo.

Samba is a Brazilian eatery located in the World Food Market and specializes in traditional Brazilian dishes, including popular street foods and a variety of savoury pastries.

The World Food Market is located right across from TMU’s Sheldon Learning Centre and is a convenient food spot for students. It houses over 18 vendors and provides visitors with a wide selection of street food delicacies from different countries.

Vendors like Samba help boost cultural appreciation among international learners as rates for out-of-country students in Toronto are rising.

According to Statistics Canada, international student enrolment rates in colleges and universities grew from seven per cent to 18 per cent from 2010 to 2019.

While Castelo relies on the World Food Market for a taste of home, Villa Saucedo goes to Kensington Market.

“I found a place called Juicy Dumpling… They have the best soup dumplings in the city. It really resonated with me because there is a place back home [in China] that serves the best dumplings, and they replicated that… I remember finding them and was so excited to go and eat them,” said Villa Saucedo.

Juicy Dumpling is well known for its cheap prices and authentic dumplings that reel in many customers daily.

Kensington Market is one of Toronto’s most recognized spots to find various worldly cuisines, where the options and lineups are endless.

“I think these restaurants are well aware their demographics are here,” said Villa Saucedo, adding that people in Toronto are more open to exploring new cultures and engaging with them.

Alongside cheap and authentic meals, Kensington is a place of comfort for her as she also discovers traditional Mexican snacks and meals that are difficult to find downtown.

“Going to Kensington Market and finding all these Mexican places that provide familiarity and Mexican snacks has been so incredibly refreshing. And I can just go there and not wait until December to see my family, so it's really enjoyable,” said Villa Saucedo.

She also finds the connection between food and one’s culture through school initiatives like the TMU residence dining halls’ “Global Eats Program.” The initiative serves different cuisines from around the world each month.

“I feel that Toronto and TMU are so diverse and everyone you meet has a different background,” said Villa Saucedo. “I feel it’s really enjoyable to share meals with other people who aren't [from] your background, but you’re able to chat and get to know each other over the meal.”

As Castelo, Villa Saucedo and Esteron said, there is a deep connection between one’s cultural heritage, identity and food cravings. Although Toronto is very different from places like Brazil, Mexico, or China, it can fulfill both the academic and cultural needs of international students like Castelo and Villa Saucedo through the power of good and authentic cultural food.